Campus life in Korea

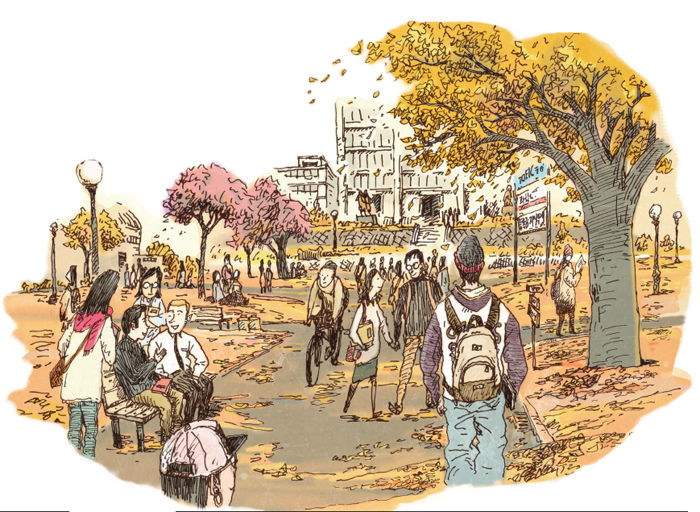

Arriving here as an instructor, my first impression of Soongsil University was of a densely populated complex of towering buildings, wide brick staircases and throngs of young students hurrying to class, relaxing on benches together or just hanging out. It’s been a few years since I was in the students’ shoes, and Korea is a long way from home, but things don’t seem to have changed so very much.

Education in Korea has a long, hallowed history, but modern schooling didn’t begin here until the arrival of Protestant Missionaries in the late 19th century. The roots of Soongsil University, where I teach, date back to 1897, when an American evangelical minister Dr W M Baird, of the Presbyterian Church began teaching a handful of students in the guest room of his home. From its modest beginnings, Soongsil went on to survive the Japanese colonial era and the Korean War to become fully accredited institution with 13,000 students, that it is today.

Located south of the Hangang River, Soongsil is accessible on subway line No 7 via its namesake station. Occupying approximately 12.9 hectares, it is a bustling, self-contained community with dormitories, cafeterias, convenience stores, an on-site bank and pretty much every other amenity you could want as a student. While it offers a full roster of science programs, engineering and humanities programs, Soongsil is known for its outstanding reputation in IT, computer studies and robotics.

In contrast to universities in North America, where campuses are sprawling affairs that eat up real estate with wild abandon, the most striking aspect of this campus is the relative modesty of its grounds. With little room to spread out, the buildings have been constructed upward, with many reaching 15 stories or more. Despite the confines of its square-shaped area. However, planners have still managed to include ample green spaces complete with pathways, manicured gardens, and abundant natural forests that alleviate the “concrete Jungle” of Seoul.

Directly across the street from campus is a strip of inexpensive restaurants, fast food outlets, bars, coffee shops and convenience stores, all catering to the university crowd. It is a lively, vibrant place, and day or night the street is filled with students blowing off steam or feverishly cramming together for the next exam.

If there is one thing all Koreans are serious about, it is education. With a literacy rate of 99%, Korea is among the most literate countries in the world. In addition to a historically high regard for education, modern South Koreans recognized education as invaluable in pulling the country out of abject poverty after the Korean War. The strategy has been highly successful, turning the country’s fortunes around from being one of the world’s poorest nations just a few decades ago to one of its richest today.

That drive to survive, followed by the drive to prosper, is reflected in a curriculum that includes English-language education from as early as elementary school, and sometimes even before. Recognizing English as the language of commerce, Korean schooling places enormous emphasis on English language skills. This fact has allowed me to come here as a teacher and experience this amazing country firsthand.

Most students I encounter have been studying English since elementary school — about 10 years. I tell them they must all be like native English speakers, which invariably elicits gales of laughter. Indeed, they can write, they understand the spoken word, they know all the grammar rules, but speaking has been a stumbling block for all but a few of them.

A pervasive shyness and lack of confidence has held them back from becoming completely bilingual. My students study all different disciplines and come from every corner of the country. Perhaps the one common thread that binds them all together is their desire to improve their English speaking skills.

My students are generally serious and attentive. At the same time, they are young, energetic adults, inquisitive about the world and looking forward to a bright future. They are the same as young people anywhere who seek a good job, love, family and security. They are predominantly alert, sensitive, polite and considerate. They are like sponges wanting to know everything about Western culture. When I discuss any aspect of Canada, be it geography, people, customs or food, they sit in rapt attention. I am always amazed by their constant thirst for knowledge.

The first week of October was “the school festival,” a week of partying equivalent to the Canadian Frosh Week. Student organizations and clubs set up tents from which they served food, beer, makgeolli(sweetish, fermented rice liquor) and the ever-present soju — a clear, strong Korean alcohol that is enjoyed in great quantities by Korean men and women of all ages (of course, adult only). Temporary stages sprang up all over campus, and entertainers were soloing on guitars and crooning into microphones long into the night. Thousands of students crowded around to dance, cheer and sing along. It was a raucous, roaring reverie that lasted for four hugely enjoyable nights.

The day starts early for my students, with even the more easy-going ones displaying a dedication that would put most Canadian students to shame. Many rise before dawn to arrive for the first class at 7:30 am Some have to get up at 5am and ride the subway for an hour to get here on time.

At that time of the day, there is little activity on campus. By the time my second class ends at 9:30 am, the campus is teeming with eager students rushing to class, taking on cell phones, texting, or meeting up with friends. Campus life is no different from any other campus at any large university, at any cosmopolitan city in the world. The big difference for me, of course, is that this is Seoul. The students are Korean. Among young people there is a huge concern with appearance and the energy spent on fashion and appearance is enormous, almost to the point of obsession. A great deal of time, concern and money is devoted to how the girls present themselves to the world. The people are generally slim, fit and dressed to impress — or excess, depending on your perspective.

Students scurry to lectures, study, chat, laugh, drink coffee, argue, dream and plan for their futures. From a very early stage, huge drive here “to find a job.” It is the great motor powering every student’s academic journey. It can’t be just any job. It has to be with a big company. The most sought-after positions are with Samsung, Hyundai, LG and other corporate behemoths. Taking a position at a lesser company seems unacceptable. Such jobs are, for the most part, considered beneath the dignity of graduates.

This is very the attitudes in North America, where graduates may take any job, anywhere just to have work while they look for the “right position.” Here, culture demands more. It could be something of an embarrassment to the graduate and his family to take a lesser position. As a consequence, many unemployed graduates sit at home waiting for opportunities. This unfortunate circumstance means that many small- to medium-sized companies have had trouble filling positions. This attitude is slowly changing, however, as the harsh reality of a new emerging economy has forced students to re-evaluate their career options.

But for now, none of this matters. The students at Soongsil are focused on getting through the next physics exam or scoring high marks on the OPI and other English proficiency tests like TOEIC. They don’t have time to ponder an uncertain future of “what if.” Right now, their lives are filled with early morning English classes and long nights in the chemistry lab. On weekends, they let loose and get ready for the Monday morning grind all over again. They have been taught from an early age that if they work hard they will succeed. Several of my Korean friends said that from an early age they have been obsessed with the idea that working hard will guarantee material success, and a good education is key.

It saddens me to see elementary school children spending countless hours at studies and neglecting the play that is so much of a North American child’s life. From grade school through university and on to their career, there seems to be no relief from the stress of study and work.

For my part, I want to do what I can to help shepherd them through to the next phase. I have been touched by every single one of them — from the academic geniuses to the artistic souls. I may have been most affected by the ones who “don’t get it” as quickly as the others. They struggle so much.

There is a pervasive attitude here of never giving up, a kind of “you can do anything” approach to the world. I think this can be partly explained by the obligatory military service that all the male students have been through. Two years of being pushed to do more with less has created a society of people who are independent and resourceful. It is inspiring to be among these young students. So much of the time I feel as though I am not the teacher here, but the student. It is a privilege to be a part of their lives.

By John Larsen | illustrations by Jo Seung-yeon | photograph by Park Jeong-roh

*The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.