A journey into steam

It’s late Friday night, almost Saturday, and the sauna my friends and I’ve come to in Apgujeong-dong is quiet and peaceful, a sharp contrast to the frenetic dance clubs and bars on nearby Rodeo Drive or down the street in Garosugil’s chic wine bars and sake houses. Those are wonderful distractions for the average weekend, but sometimes you want something a little more relaxing, something to soak away the gritty workday and soothe bones weary from Seoul’s fast-paced life.

There are many saunas, spas, and jjimjilbang scattered throughout the city. We’ve come to my friend’s favorite one, an upscale facility hidden in a dark glass skyrise. The man at the counter gives us three plastic bands with numbers on them. Mine is 110. We pass through a curtain and down a small hallway to reach the changing room. The little number on our bracelets is the key to our lockers. I somehow manage to lock mine a couple of times before getting the trick down.

As we are stashing our clothes, my friends and I are the only ones in the locker room. Soon, we are as naked as the day we were born; we head to the shower room. The room to shower and bathe is sparsely populated; a handful of weary salarymen are boiling in the hottest of the three baths. Another man is showering along one of the walls. Typically, one showers first before slipping into the large stone baths found in nearly all saunas in Korea. One of the things that makes this particular sauna better than most is the showers themselves: Unlike at the majority of baths, these stay on until you turn them off. Nearly everywhere else, they turn off every minute. Here, you can luxuriate under a torrent of perfectly heated water. Soap, shampoo and even conditioner are provided, though the germophobe will want to bring his own. Some saunas sell amenities such as disposable razors. Luxuriate is the operative word here.

After the shower, I opt for the merely scalding bath; there is no temperature reading as there are at many saunas, but it’s probably around 40C. There are two other baths here: an even hotter bath with an herb infusion, and a cold bath. Some spas will have others as well. Often the herbal bath — jasmine is common — will be a reasonable temperature, in the upper 30s. A few saunas have individual baths in addition to the ubiquitous large basins, which can fit 10 to 30 people.

For several minutes, my comrades and I sit and soak in silence, our thoughts drifting away with the plumes of steam. My friends had just come from the basketball court, weary and sore from the exertion. The bath is a perfect end to their rigorous day. Others are now arriving in the shower room, more salarymen fresh fromhoesik: the mandatory, fun Korean business dinners that demand both drinking and noraebang (Korean karaoke). Like us, they are quiet; the sauna feels like a sacred place, a temple where the repentant come to scour away their sins and be reborn in the searing waters.

Eventually though, we do start conversing. One of my companions is a Japanese executive who visits Seoul regularly. Surprisingly, he’d never come to a Korean sauna or jjimjilbang before, though he had been to public baths and spas abroad. “In Russia, after sitting in the hot bath, everyone gets out and dives into the snow,” he tells us.

“Dives in naked?”

“Yes!”

This sauna has no snowbanks, but it does have an icy-cold bath. Well, perhaps icy is a little strong, but it is certainly cold. Only one of us has the fortitude to get in. “It’s good for circulation,” he insists. I’m fine staying in the warmth, thank you very much.

One of the main attractions of this sauna is the outdoor bath. Adjacent to the shower room is a partially enclosed patio. A sharp wind, kisses from Siberia, strikes us as we make our way to this bath. Unlike the ones indoors, it is enclosed in wood. Copses of bamboo grow around the bath, muffling the nightscape sounds of the city. We quickly climb into the bath and resume our luxuriating and conversation. The icy wind now feels invigorating as we sit half submerged in the water. The appropriate Korean word for this sensation is siwonhaeyo (refreshing). After a while, our skin wrinkly as a pug’s, we decide to check out the rest of the facility. In fact, the floor we are on is the sauna proper; below us is the jjimjilbang. A jjimjilbang is something like a spa, community center, recreation center and cheap hotel wrapped together. First though, we put on the uniforms provided. Such facilities always offer uniforms, often a t-shirt or robe/shirt and shorts — in coed jjimjilbang, the men’s and women’s uniforms are different colors.

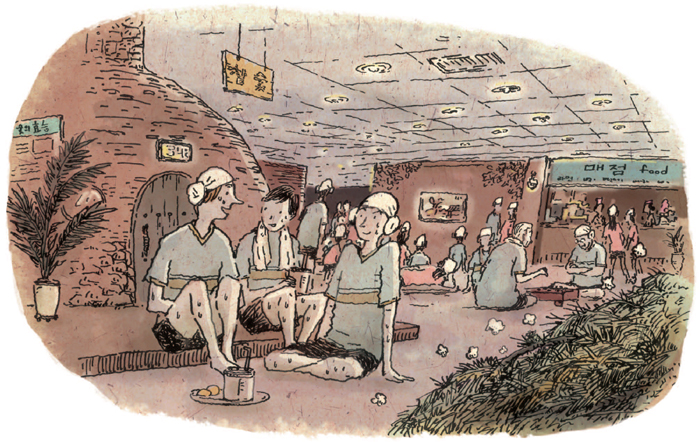

Dressed in the earthy beige of the sauna’s threads, we head downstairs. There are more people here than there were in the baths, but it’s still reverentially quiet. A few older men are playing janggi (the Korean equivalent of chess), a couple of guys are laying on the floor in front of a large television with the volume on low. Others are sitting at the bar of the tiny coffee shop or in the little restaurant next to it. Our first destination, though, is the oven. The oven, as we call it, is a large room constructed like a traditional stone and thatch building, the walls convex and ending in a conical point at the top. It is stupefyingly hot inside. We have to climb in through a hobbit-sized door. A large hourglass sits on the mats in the middle of the room. We flip it over and settle in. Our Japanese friend has never experienced this.

“The air’s heavy; it’s a little hard to breathe,” he tells us when we ask what he thinks of it. “Yeah, that’s normal the first time,” we assure him. We are conversing, quietly, in English; another man comes, sits for a moment, and then leaves. The last of the sand slips away in the hourglass. We scamper out of the oven and towel away the sweat. It felt good to sweat in there, expelling untold levels of toxins, as some say.

“What’s next?”

“The ice room.”

Just to the left of the oven is a walk-in freezer that would not be out of place in any number of restaurants. The air is still and crisp, but despite the frost-caked coils lining the walls, it doesn’t feel cold exactly. Again, we need the Korean word: siwonhaeyo! After a while, 10 minutes maybe — time seems like such an alien concept in this palace of relaxation — we do begin to feel the room’s deep chill working its way into our flesh. We adjourn to the next room, the charcoal room. It’s another dry sauna room, not as hot as the oven but still quite warm, with the heavy scent of aromatic wood and charcoal permeating the air. And a TV. A couple of younger men sit watching the news. We stay long enough to get the general idea and then retire to the coffee bar.

The menu is fairly extensive, with a variety of juices, teas, coffees, and other beverages. Our Japanese friend orders tomato juice, a lassi for me, and simple green tea for my other friend. The tomato juice and lassi are made from scratch.

People leave their belongings upstairs in their lockers, so the sauna charges our electronic bracelets. We aren’t hungry but we do take a look at the little restaurant’s offerings. Basic Korean food — bibimbap, seolleongtang, doenjang-jjigae — are, of course, the specialties of the house.

We’ve been in the sauna and jjimjilbang for quite a while now. More men have come in and are sleeping on the mat by the large TV. At this jjimjilbang, the provided pillows are small firm rectangles. Other places often use pillows — and I use this word generously — made from beaded bamboo strands or even wooden blocks. For those that need a darker and quieter space, a room off the main area is set aside for sleeping.

If this were a coed jjimjilbang, the central space would be shared by both men and women. While our jjimjilbang is more luxurious, and thus more expensive than most, it is still considerably cheaper than a hotel. Thus, jjimjilbang are popular for many workers and travelers. Should a business dinner run quite late, it is often better to crash at the nearest spa than to try catching a taxi to the suburbs or driving drunk. Whole families can also be found at night in many jjimjilbang, especially the large and famous ones in the far reaches of the peninsula.

Our drinks finished and our energy wavering, we decide to make our way back upstairs. Another quick shower and a few minutes in the bath to wash away the dry, sauna-induced sweat finish us up. Just out of the shower room are all the basics needed to make ourselves presentable: hair dryers, gels and mousses, and the like. Some jjimjilbang have barbers available during the day. Professional masseuses are often on staff as well. Coed jjimjilbang usually have nail technicians, play rooms for kids, PC rooms and a host of other amenities. It is entirely possible for a family to spend a whole day in a jjimjilbang and never get bored.

The only thing we missed in our visit, I realize as we’re dressing, is the salt room. Salt rooms vary from sauna to sauna. In some, the room — a hot, dry sauna — is liberally coated in coarse salt. In this one, however, there is a large bowl of salt outside the room. It is the patron’s responsibility for gathering his own and then scouring his body with the white pillars. This is supposed to help exfoliate the skin, draw out excess water and toxins, and improve your skin’s health overall.

“Whenever I go to the sauna, I sleep like a baby afterwards,” my friend explains to our Japanese companion as we’re getting into the car. I take a look back. From the outside of the jjimjilbang’s building, you’d never know it was there. Even the outdoor bath’s enclosure is completely hidden from the outside. I wonder how many other wonders the city hides within its glass and concrete facades.

By Chris Sanders