The Value of the Dongui Bogam and its Status in East Asian Medicine

Historical Background

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, East Asian Medicine developed a new logical model about medical information on the basis of Neo-confucianism. At the same period, it increased the amount of medical information by gathering data from all over East Asia, which was published into books and propelled by the development of printing culture. However, the problem of increasing medical information was that although the accumulation of information had significance as a database, there was a lack of knowledge about how to utilize the data for actual treatment. In other words, medical information, which was more concise and effective and in a more compressed form that would be readily applicable in medical practice, was necessary. After the sixteenth century, the medical books that met the purpose of practical treatment began to appear. In China, the Yixue Zhengchuan『醫學正傳』(Orthodox Transmission of Medical Learning) published in 1515 and the Yixue Rumen『醫學入門』(Primer on Medical Learning) published in 1575 are representative. In Japan, the Keitekishu『啓迪集』(Compilation for Enlightenment) written by Manase Dosan (1507–1594) was published. Among such kinds of the medical classics, the Dongui Bogam『東醫寶鑑』(Treasured Mirror of Eastern Medicine), published in the Joseon in 1613, is the most representative. Among the therapeutic techniques using herbs and acupuncture, which had been accumulated in various forms until that period of time in East Asia, the especially useful methods in medicine were properly selected and contained in the Dongui Bogam: therefore, there remain quite a number of treatment methods that are still useful up to the present in clinical fields.

The Value of the Dongui Bogam

The Dongui Bogam covers all cultural contents about healing in that period of time, not only including contents about the formation of human beings and about meditation training, but also the record of diverse diseases in various ways, high quality-knowledge of the treatment of diseases, and the methods easily available to ordinary people. Moreover, it contains in-depth discussion about how the people of the Joseon period understood and accepted Chinese Medicine in the dynamic relationship among the world of East Asian Medicine, and about how the medical philosophy of the Joseon period could be distinguished from that of China. Likewise, it has the significance as the sum compilation through which we can understand the range of East Asian Medicine during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in every subject area which has points of contact with medicine, such as natural science, medical culture, medical techniques, medical psychology, and medical philosophy. Furthermore, since it contains a variety of data sources from which we can assume the method of discrimination between imported herbs and domestic herbs, the new nomenclature of native herbs, and the distribution and utilization of herbs, not only the health care providers but also the researchers in various fields are currently conducting studies based on its contents with great interest. The publication of the Dongui Bogam was first supervised by the state and as such is a medical work interlinked with the establishment of the nation’s health care system and must be viewed from the position of the state, which ought to continuously secure and update this invaluable database of medical information.

The Dongui Bogam‘s Influence in East Asia

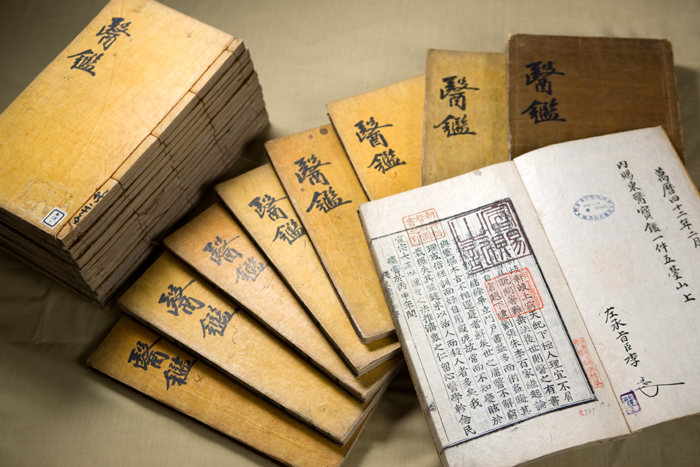

Since its publication in 1613, the Dongui Bogam has become the representative text of Korean Medicine. Medical books that came out later are all connected to the Dongui Bogam in some way. The Gwangje Bigeup『廣濟秘笈』(Secret Satchel for Broad Benefit) and the Jaejung Shinpyeon『濟衆新編』(New Volume for Benefiting the Populace) are clear examples that show the Dongui Bogam‘s strong influence on Korean medical community. TheDongui Bogam was the most read medical text among Korean medical practitioners in the next few centuries. In the 19th and 20th centuries, a number of publications that condensed the Dongui Bogam were printed. It was also a one of the most fundamental of Korean Medicine textbooks since the liberation in 1945.

The Dongui Bogam affected other countries that used Chinese characters as well as Korea. It was republished dozens of times in China and Japan, and became well-known farther abroad to Vietnam, Manchuria, and Mongolia. Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684–1751), the 8th Shogun of Japan, was well-versed in medicine and was famous for always carrying a copy of the Dongui Bogam with him. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Dongui Bogam was easily accessible around bookstores in Beijing, the capital of Qing Dynasty. The following is a list of different editions the Dongui Bogam published in premodern China and Japan. In addition to these publications, there are numerous cases where the Dongui Bogam was exchanged or granted as a diplomatic present from the Joseon dynasty to foreign nations.

Japan

1724 (Japan Kyoho First Edition, 日本享保初刊本) 1799 (Japan Kansei Second Edition, 日本寬政重刊本)

China

1763 (Qianglong Biyutang Edition, 乾隆壁魚堂刊本) 1766 (Qianling Lingyu Preface Edition, 乾隆凌魚序刊本) 1796 (Jiaqing Dunhuatang Edition, 嘉慶敦化堂刊本) 1796 (Jiaqing Yingdetang Edition, 嘉慶英德堂刊本) 1796 (Jiaqing quchengtang Edition, 嘉慶聚盛堂刊本) 1797 (Jiaqing Dingsi Year Edition, 嘉慶丁巳刊本) 1821 (Qingyunlou Edition, 慶雲屢刊本) 1831 (Zishantang Edition, 資善堂刊本) 1831 (Daoguang Fuchuntang Edition, 道光富春堂刊本) 1847 (Daoguang Chongshuntang Edition, 道光崇順堂刊本) 1885 (Guangxu Jiyou Year Edition, 光緖己酉刊本) 1885 (Baofang’ge Edition, 抱芳閣刊本) 1877 (Guangxu Jinwentang Edition, 光緖近文堂刊本) 1889 (Guangxu Jiangzuo Editon, 光緖江左刊本) 1890 (Saoyeshanfang Wood Edition, 掃葉山房木版本) 1890 (Guangxu Mincuixiang Preface Edition, 光緖閔萃祥序刊本) 1890 (Jiaojingshanfang Edition, 校經山房石印本) 1890 (Jinzhang Tushuju Edition, 金章圖書局石印本) 1890 (Qianqingtang Edition, 千頃堂石印本) 1890 (Guangyi Edition, 廣益石印本) 1908 (Saoyeshanfang Edition, 掃葉山房鉛印本) 1912 (Jinsushuju Edition, 錦素書局石印本) 1917 (Guangyushuju Copy Edition, 廣益書局影印本) 1917 (Jinzhangshuju Copy Edition, 錦章書局影印本)

The Dongui Bogam and Korean Delegation

In 1599, after seven years of war, the relationship between the Joseon, Korea, and Japan finally entered a new phase. The Joseon demanded that the prisoners of war be released and Japan made an apology for the invasion. Joseon Korea decided to send delegations in response to Japan’s formal apology. Since then, the diplomatic relations between the two nations began to improve. Under the rule of the Shogun Tokugawa, it was very important to receive envoys from Joseon Korea in order to stabilize his regime. Accordingly, he could gain acknowledgement from both the Japanese people and neighboring countries.

Japan had regime change twelve times from 1682 to 1811. Every time, the Joseon dispatched a large number of envoys with several hundred people including a vice-minister of government. The missions were originally sent for the repatriation of prisoners captured during the war. However, as time passed, the act of sending delegations grew to be a cultural event with musical troupes and dancers accompanying the delegation. The path by which the missionaries passed remains as a significant cultural heritage site in Japan. The delegations also included scholars and physicians. This provided an opportunity for Joseon Korea culture to be introduced to Japan.

In the field of medicine, in particular, Japanese physicians across the nation gathered in teams and interviewed Korean physicians. They even wrote down the content of these conversations in books. Currently, there remain more than forty records of the medical dialogues between Korean and Japanese physicians in Japan. The most representative of all these dialogues is the one about the Dongui Bogam and Korean ginseng. Korean ginseng was an expensive herb at the time. Japanese medical practitioners were largely interested in learning advanced techniques of cultivating and gathering Ginseng, and its application from Joseon’s physicians. Likewise, theDongui Bogam became popular in Japan after being published in 1613. Japanese doctors who interviewed Joseon’s doctors were very curious about this book. The complete set of the Dongui Bogam was reprinted. Some books also edited and published just the herb-related parts of the Dongui Bogam, and there were a lot of specialists as well of the Dongui Bogam. Furthermore, a technical book researched the production of herbs inDongui Bogam twice in 1718 and 1721, and systematically compared Japanese native herbs with Korean herbs. The purpose of the research was to adopt the treatment methods of the Dongui Bogam and make use of them with local Japanese herbs. This is just one of many possible examples that proves the practical value of the Dongui Bogam when it was first published and circulated throughout East Asia.

*This series of articles about the Dongui Bogam has been made possible through the cooperation of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.