New Zealander hikes North, South Korea

Roger Shepherd is an avid outdoorsman who has hiked the length of the Korean Peninsula, both North and South. Hiking the length of Korea consists, essentially, of hiking the Baekdudaegan.

The Baekdudaegan (백두대간, 白頭大幹, or “Great White-Topped Mountain Range”) is the heart of the Korean Peninsula. It is an unbroken chain of mountains that runs from the Chinese-North Korean border all the way to Jirisan Mountain in the south.

Shepherd has so far published two books on the Baekdudaegan mountains. He co-authored a hiker’s trail guide in 2010 and late last year came out with a coffee table book of Baekdudaegan photographs.

Korea.net reported on his books earlier.

First English Baekdudaegan guidebook published

August 6, 2010

https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=82232

New Zealander captures Baekdudaegan with his camera

December 26, 2013

https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/People/view?articleId=116621

Shepherd recently sat down with Korea.net to talk about his love of the mountains and his newest book.

Korea.net (K): Please introduce the Baekdudaegan mountain chain to our readers.

Shepherd (S): The Baekdudaegan is the geographic backbone of the Korean Peninsula. It gnarls its way south from Korea’s highest peak, Baekdusan Mountain (2,744 meters) (백두산, 白頭山, White Top Mountain), on the Korean border with Manchuria, for about 1,700 kilometers to the Cheonwang-bong Peak on Jirisan Mountain (1,915 meters) (지리산, 智異山, Unique Wisdom Mountain). It is a pure continuous ridge that is never broken by water, therefore making it the watershed for all the major rivers of Korea.

Two of those rivers begin at Baekdusan Mountain. One is the Amnokgang River (압록강, 鴨綠江, the “Boundary Between Two Countries” River), which flows to the south and southwest, and the other is the Dumangang River (두만강, 豆滿江, the “Myriad” River), which flows to the north and northeast. These two rivers form the border between Korea and China, making Baekdusan Mountain the only land bridge that connects Korea to the rest of the Asian continent and eventually to Europe and Africa.

Holistically, the Korean people see the Baekdudaegan as the provider of Korea’s vital energies. The ridge is seen to act like a spine, transmitting natural energies throughout the landscape via its intricate mountain network, like a huge central nervous system. Traditionalists would believe that to damage its energy is to damage the vitality of the Korean people.

Roger Shepherd, armed with camera, sits atop the Cheonwang-bong Peak (천왕봉, 天王峰, King of Heaven Peak), the highest point on Songnisan Mountain

(속리산, 俗離山, Apart From Society Mountain), in Chungcheongbuk-do (North Chungcheong Province). Other “King of Heaven Peaks” exist on other mountain tops. (photo: Roger Shepherd)

K: What is the best way to preserve the Baekdudaegan? Where lies the balance between a modern park and the natural environment?

S: I think Korea can acknowledge that it is heavily populated, with just over 50 million people occupying 35 percent of its topography, whilst the rest is mountain. This population fact makes natural preservation of large tracts of land, in a landscape that is riddled with infrastructure, rather difficult. Korea’s narrow land size means that it doesn’t have huge tracts of land that are void of human habitation, unlike some other nations.

In turn, what the people need to do is to find a way to manage their coexistence with nature in a modern green way that allows educated citizens to access nature without damaging it. I think to deny people access to their mountainscape is nigh impossible. This isn’t an obstacle. This is a challenge.

Korea can create a model for the world and show how to build a sustainable environment that holistically incorporates both mankind and nature. The eco-management of the Baekdudaegan as an international hiking trail or biosphere that symbolizes traditional and modern Korean identity can be done, but only with a national effort to preserve its status as the foundation of Korea’s ecology.

K: What are a few of your most beautiful spots along the ridgeline or along one of its adjoining mountain ranges?

S: Mountain-wise, the section of the Baekdudaegan from Songnisan Mountain (1,057 meters) (속리산, 俗離山, Apart From Society Mountain), in Chungcheongbuk-do (North Chungcheong Province), eastward to Taebaeksan Mountain (1,567 meters) (태백산, 太白山, Great Pure Mountain) in southern Gangwon-do (Gangwon Province), has always been one of my favorites.

Another highlight of the Baekdudaegan is the interaction you have with other hikers and some of the locals in the nearby villages, especially between Jirisan Mountain in the south (1,915 meters) (지리산, 智異山, Unique Wisdom Mountain) and northward to Deogyusan Mountain (1,614 meters) (덕유산, 德裕山, the Mountain of Abundant Morality) in Jeollabuk-do (North Jeolla Province).

The sunrise from the Daecheong-bong Peak (대청봉, 大靑峰, Great Blue Peak), sitting at 1,708 meters atop Seoraksan Mountain (설악산, 雪嶽山, Snowy Peak Mountain). (photo: Roger Shepherd)

K: Similarly, what are some of the more grueling hiking sections, either along the ridgeline or along one of the connecting ranges?

S: One of the toughest days was my first day along the trail, with a 1,300-meter climb to the Cheonwang-bongPeak (천왕봉, 天王峰, King of Heaven Peak), the highest peak on Jirisan Mountain (1,915 meters) (지리산, 智異山, Unique Wisdom Mountain).

It should be noted that the Baekdudaegan is actually a very tough course. Nothing is ever flat on it. Korea’s mountains, although not over 2,000 meters, are, however, famously sharp and steep. Some foreign hikers have come here and been rudely surprised at the demand of the terrain. The rewards, however, are unique. When you walk along the Baekdudaegan, you have panoramic views of the entire peninsula. Waves of mountains swim endlessly all around you. It’s an amazing sensation to let the world rotate under your feet whilst you treadmill along the great ridge of Korea.

K: Tell us about your most recent book.

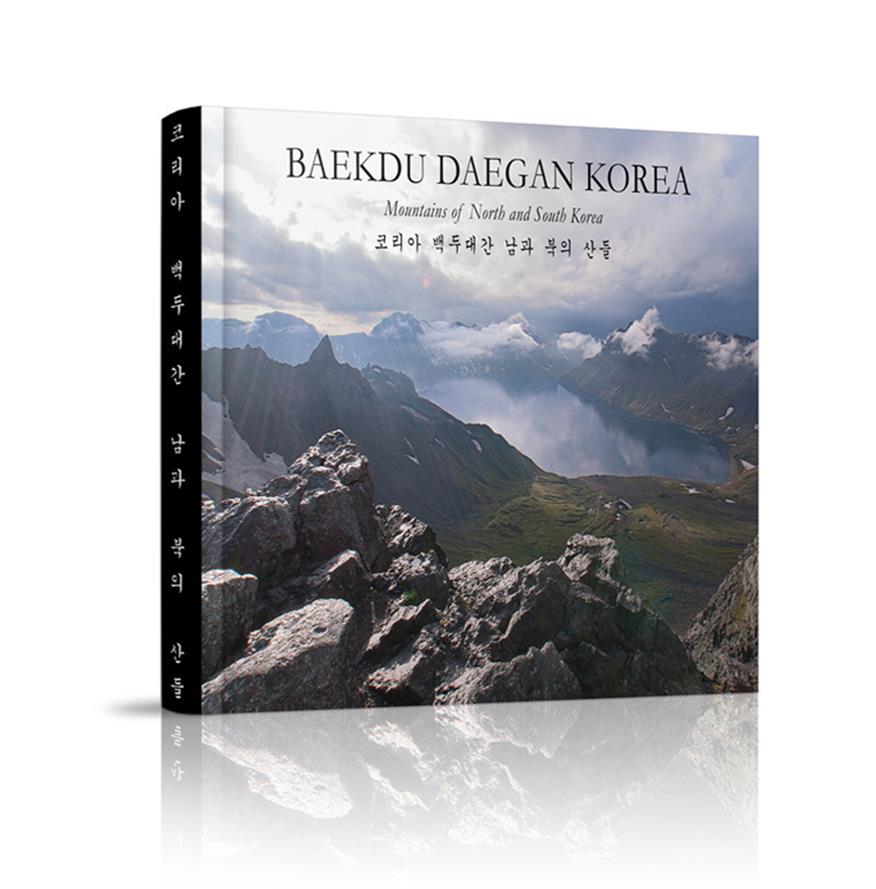

S: “Baekdudaegan Korea: Mountains of North and South Korea” is a photo-art book. It’s a completion of five years of exploration of the Baekdudaegan in both North and South Korea. When I decided to make this book, I knew it would have been pointless to do it if it only contained images from the southern section of the ridge. I was very fortunate to be granted access to the northern section of the mountains. I spent about three months in North Korea, between 2011 and 2012, traveling to about 24 different mountains along the ridgeline there. I personally see my book as more of a legacy, which one day may be looked upon as being the first document to record the Baekdudaegan as an entire entity, which is what it is.

“Baekdudaegan Korea: Mountains of North and South Korea” was published in Seoul last year.

The book comprises of photographs taken along the Korean Peninsula’s mountain backbone. (photo: Roger Shepherd)

K: For a beginner hiker here in Korea, what would be the best way to experience the Baekdudaegan on a weekend-by-weekend basis?

S: Well, I suppose they should purchase the English version of “Baekdudaegan Trail,” the trail guide book, and begin studying each section of the ridge that’s recorded in that book. As it will be mainly weekend hiking, they could then start in any season. They could walk it in either direction, depending on where they live. Ideally, if there are two or more people and if they have vehicles, then they could leave one vehicle at their proposed end point, to avoid having to hitch back to their vehicle that’s one-day away. Or they could join any one of the many clubs that hike the trail on weekends. That would actually be quite a cool experience and a good story to tell, as well.

Roger Shepherd stands at the foot of Baekdusan Mountain (2,750 meters)

(백두산, 白頭山, White Top Mountain) in North Korea in June 2012. (photo: Roger Shepherd)

The crater lake atop Baekdusan Mountain (2,750 meters)

(백두산, 白頭山, White Top Mountain) in North Korea in June 2012. (photo: Roger Shepherd)

K: How was it to work with North Korean authorities?

S: Despite North Korea’s poor international image as portrayed in media, I have always found the North Korean people to be outstanding people and very “Korean”. They were friendly, humble, dignified and showed tremendous etiquette. They have never let me down in any of the promises they made to me. They worked very hard to achieve the objectives and they delivered all the time. This is a Korean trait, which can be experienced in all parts of Korea.

K: What were some common traits you saw between modern day North Korean culture and modern day South Korean culture?

S: I think what needs to be made clear, for outsiders looking into Korea, is that the division of Korea has in turn created two different ideologies of Koreans that have both been influenced at some stage by policies that are foreign to the Korean people. They are, in theory, the two newest countries in the world.

In a sense, the best way to understand or to see Korea and its people is to look into its past, when it was one nation. This is a part of Korean history that neither the North nor the South can deny. They both agree on it.

As an outsider, when conversing with people from the North and the South, it is often a good idea to relate to them by discussing a period when they were all one nation. This not only impresses them with your background knowledge, but also brings out common “Korean” traits. This, in fact, makes them Korean. Sixty years of division is not actually a long time for a kingdom that has shared a homogenous language and tradition since the last Ice Age. As a foreigner, I think we should always be looking for ways to let the Koreans be “true” Koreans again. The foreign vices they currently have, be it either capitalist or socialist ideals, are not necessarily Korean virtues.

K: How about some differences between North and South Korea?

S: This is always an interesting observation for me. The question, as I mentioned in my above answer, is, ‘What actually is a Korean?’ Does a Korean from the South or North necessarily reflect what a Korean is, or should it be based on their natural demeanor according to history, art and literature from a period when they were one unoccupied nation?

Is a kid sitting on the subway staring into his smartphone with little or no knowledge about shamanism, the Three Kingdoms period or the Korean War any more “Korean” than a kid from the North with no smartphone? It is not the materialistic possessions we have that define us. It is the inner traits that we have as humans that define us according to our language and culture. Socially, I didn’t sense much difference between a Korean from the North and one from the South, other than that it is a little harder for a person from the North to open up to you, as you a very much an outsider, compared to the South which has a political alliance with most Western nations.

K: Finally, what do you have planned for 2014 and 2015?

S: I have some interesting plans for 2014 and onward. I would like to see my business expand into an inter-Korean venture. I would like to start taking tourists on excursions into North Korea from South Korea, and vice versa.

My first project, hopefully, will be to take a bunch of cyclists from Seoraksan Mountain (1,708 meters) (설악산, 雪嶽山, Snowy Peak Mountain) in Gangwon-do to Geumgangsan Mountain (1,638 meters) (금강산, 金剛山, Diamond Mountain) in the North Korean part of Gangwon-do. This would include hiking a 1,708-meter and a 1,638-meter mountain.

Also, I recently got the North Koreans to agree to let me make a nature and wildlife documentary on Baekdusan Mountain and its surrounding region. The deal is that the project will be funded in the south and edited in the south for a Korean audience. The camera crew would be North Koreans, with maybe one world-class foreign camera operator. Working with MBC Korea, we are hoping to receive funding for this project through the Korea Communications Commission. It would be a great project that all Koreans could enjoy and feel nationalistic pride with.

My interest in Korea has expanded naturally. Through my work on the Baekdudaegan, I now see Korea as one nation currently experiencing a period of turmoil that will one day end peacefully and naturally when they are in a position to let that happen. Foreign governments and foreigners should also work toward making that happen, rather than trying to dictate the situation to them in a way that may also suit their own agenda in the region.

Duryusan Mountain (2,309 meters) (두류산, 頭流山, Streaming Top Mountain) is in Baegam-gun, Hamgyeongnam-do (South Hamgyeong Province),

in North Korea. (photo: Roger Shepherd)

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer