Converted to kimchi

Despite living just a few kilometers from a big Koreatown in the United States, Charles Montgomery knew practically nothing of Korea or its food. But when an opportunity arose to try Korean cuisine, with a Korean student studying nearby, Montgomery discovered how much he liked Korea’s barbecued pork, zingy, indigenous liquor, and the unforgettable spicy condiment that comes with everything. Now teaching English translation at a university in Seoul, Montgomery’s passion for all things Korean continues to grow — especially for Korea’s fiery, fermented favorite, kimchi.

The first bite of kimchi is one of my favorite moments during any meal. From hot and spicy, to refreshing and even cool, I never know exactly what kimchi I will taste. In homes or restaurants, kimchi comes to the table with the rest of banchan (side dishes) and I sneak a first peek. Is it fiery red? Elegant white? Does the cabbage look crisp, or cling to the plate? Is it cabbage or cucumber? Then, chopsticks descend, kimchi ascends, and my mouth closes. Taste-buds begin to dance and a rush rises up my nose and into my brain. The meal is going to be good!

This is not how I used to begin my meals. Although I grew up in California, less than 20km away from the Koreatown in Santa Clara, I knew little about Korea. Passing through Koreatown I couldn’t see a difference between signs in Hangeul (Korean alphabet) and the signs I saw in Japanese or Chinese neighborhoods. And the food? I had no idea.

Many years later I ran the night tutoring program at Chabot College in Hayward. One of the tutors was Ed Park, a young Korean. Ed was studying for his MA in Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, and tutoring because he knew it was a good way to improve his own English skills. One night he asked me if I’d like to have a beer, and after shutting the center down, we went out for drinks and food. Our friendship developed, and eventually Ed asked if I had ever eaten Korean food. I said no, so he took me out for a meal.

We began with samgyeopsal (barbecued pork) and soju (a distilled Korean spirit), a combination that, Ed helpfully pointed out, was quite similar to barbecues in the Western world. But then, out came banchan. This, I had never seen before: Little plates covered with different kinds of (to me) very unfamiliar food. On one of those plates there was something red and sort of scary looking.

Ed pointed to that plate and asked the question that I’ve been asked scores of times since I have lived in Korea, “Do you know kimchi?” By the end of the evening, I thought I could answer that I did. In fact, I my knowledge of the inimitable side dish had only just begun.

Several years later, I now know that kimchi, the “soul food” of Korea, is a simple dish with a deep role in Korean culture. It is so embedded in the Korean psyche that instead of saying “1, 2, 3, cheese!” when taking photos, Koreans say, “1, 2, 3 kimchi!” The fiery side dish has roots stretching at least as far back as the 7th century, with the first written mention of it appearing nearly 3,000 years ago.

Kimchi is, along with rice, the staple of every Korean meal, and so important that in many Korean homes (and in the homes of ethnic Koreans across the world) there is a special “kimchi refrigerator” to hold it. But kimchi is more than just food to Koreans. It also represents solidarity, community and survival.

Perhaps most importantly, kimchi is the food that has sustained generations of Koreans. When the cold winds of winter rushed down the Korean Peninsula, it was impossible to grow crops. In order to survive this cold season, Koreans had to develop a nutritious food with a long shelf life.

Kimchi was the answer. Not only did the fermentation process preserve the food, the final product was also a nutritional bonanza: high in fiber, low in fat, loaded with vitamins A, B and C, and also containing lactobacilli, a “healthy bacteria” that aids digestion and may even prevent yeast infections. There are hundreds of kinds of kimchi, made of vegetables including cabbage, radish, green onion, cucumber and chili pepper.

Each region of Korea has its own special, representative version. Besides baechukimchi, well-known kimchi include the crunchy kkakdugi, a kimchi made with cubed radish; the scallion based pa-kimchi; and a hot and spicy kimchi named oi-sobagi.

The culture of gimjang

Kimchi is generally divided into two types, seasonal, which is made from locally sourced vegetables, intended for immediate consumption, and gimjang, which is made in large quantities in late autumn. Kimchi’s characteristic red color didn’t actually appear until sometime after 16th century, and certainly by 19th century, when the red chili was introduced to Korea and red chili pepper flakes were added to the kimchi recipe. The latest addition to the kimchi we know today was the introduction of the Chinese cabbage in the 1900s.

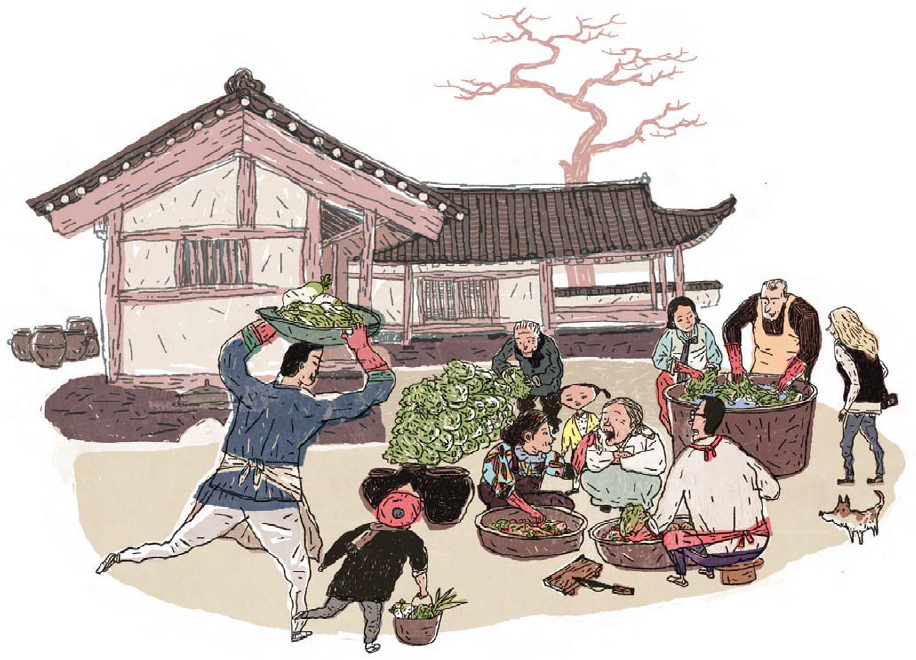

Kimchi preparation is uniquely Korean. Following the cabbage harvest in fall, Korean villages would traditionally spend part of November conducting gimjang, a communal process of kimchimaking that united generations in preparation for the winter. This tradition continues today, with some families buying hundreds of heads of cabbage, as well as the other ingredients necessary to make kimchi. Women wash and trim the produce, prepare the brine, painstakingly interlace layers of ingredients and carefully fold the cabbage before storing it in kimchi pots for fermentation. Gimjang goes beyond mere food-making, however, as it is also a social event, in which Koreans socialize at all steps in the process, and then help each other prepare kimchi. As I came to know kimchi, I came to learn these things, and others, about Korean culture.

Driven by an interest in Korean literature and culture, I arrived in Korea 10 years after my introduction to kimchi. I landed in Daejeon and my personal “kimchi education” really began. While I was fairly used to baechukimchi as a side dish, I was mostly unaware of the wide range of kimchi and completely unaware of the many dishes that feature kimchi as an ingredient. Imagine my surprise when I discovered “summer kimchi” (e.g. stuffed cucumber kimchi), which is frequently eaten before it has time to ferment. White kimchi (which leaves out the chili pepper) was also a bit of an eyeopener, but refreshed me during Korea’s hot summers.

At first, I did my exploring alone. But my wife followed me to Korea six months after I arrived. In the United States she had been afraid of kimchi’s strong taste, but once in Korea she quickly came to love it. I can still remember the first time we sat down together and, while we waited for our galbitang (beef soup) to arrive, she sank a pair of tongs into the communal kimchi-bowl on the table, slapped a hefty sized pile of kimchi onto a banchan plate, scissored it once, lifted a piece to her mouth and ate it. She looked at me and said, “It’s good, it has a kind of hot aftertaste.”Now, it’s impossible to get my wife to eat plain rice.

To me, certain foods seem to go together naturally. In the United States we have: pizza and beer, cookies and milk, turkey and stuffing, and, macaroni and cheese. Now I have added to these eternal combinations, kimchi and rice (although my wife does not drink I’d also like to say a kind word about samgyeopsal and soju as this kind of special pairing).

We also discovered dishes with kimchi in them that we had been unaware of. Dubu-kimchi (tofu and kimchi) pairs soft, silky tofu with chewy, tangy kimchi, and is also excellent chopstick practice as the tofu can be quite elusive.Kimchi-jjigae is a spicy stew made with kimchi, pork and tofu and is a perfect dish for a cold Korean night. Kimchi-bokkeumjeon is savory pancake, crunchy at the edges and chewy inside, made with kimchi, flour, water, eggs and sometimes seafood. Mix in a bowl, panfry, and eat!

Last but not least, the delicious “fast food” kimchi-mandu are dumplings filled with kimchi, tofu and often pork and glassy noodles called dangmyeon. They can be boiled, steamed, fried, or added to soups and stews. A little bit meaty, a little bit tangy, they are great for adding a bit of substance to everyday soups. I like to buy my kimchi-mandu from the vending trucks that park on corners in many neighborhoods in Seoul.

Now, of course, after the initial success of “kogi” taco-trucks in Los Angeles and elsewhere, kimchi has gone international. World famous restaurants such as New York’s Momofuku serve it in dishes like kimchi-jjigae with rice cakes. Online you can find recipes for making kimchi as well as a wide variety of kimchi inspired dishes, even including kimchi-deviled eggs!

In Seoul this year, I visited the Kimchi Sarang Festival and was amazed at the variety of gourmet dishes that chefs had concocted using kimchi. Here, also, I got to watch the creation of kimchi and felt as though I was watching something timeless.

I have been in Korea for three years and will stay at least another two. My wife and I have not determined where in the US we plan to move to, but we have decided one thing — we won’t move anywhere there isn’t a Korean market or restaurant. 5,000 years of food tradition has converted us!

By Charles Montgomery | illustrations by Jo Seung-yeon

*The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.