Korean classroom is based on an age-old tradition of learning

Foreign observers of Korea often comment on the country’s passion for education and its role in Korea’s remarkable development over the past 50 years. Experts visit Korea to study its education system, looking for ideas that might be applicable back home. The current success of Korean education, however, has deep roots in a long tradition of respect for learning and respect for teachers.

Andong’s Dosan Seowon, one of the greatest private Confucian academies of the Joseon Dynasty. © Yonhap News

A Culture of Learning: The Way of the Seonbi

To understand the roots of Korea’s educational success, it is first necessary to understand the “seonbi spirit.” A combination of honest spirit, dignity and nobility of character, the way of the seonbi was the central ethos that drove Korean culture for centuries. Kyung Hee University professor Emanuel Pastreich, an expert on comparative Asian studies, goes as far as to argue that the Korean seonbi is, “an ideal for the integration of learning and action, proper behavior and moral commitment,” and could serve as a trans-cultural archetype, like Japan’s samurai or the European knight.

The word seonbi literally means, “a man of good will and learning.” Idolized as the ideal man during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the seonbi were scholars who, despite their prodigious learning, often forsook lives in the civil service—the surest way to fame and fortune in those days— to pursue lives of fidelity, principle and self-cultivation. The goal of the seonbi’s life was to put his learning and education into practice.

According to Confucian teachings, a seonbi does not abandon his virtue to live; instead, he is willing to give up his life for it. Indeed, throughout the Joseon Dynasty, countless scholars endured banishment or even death because they chose to remain true to their principles, rather than compromise for personal gain. Though many seonbi did, in fact, take positions in the government, to them, government service was not a goal in and of itself. Rather, it was an opportunity to realize their virtue and conviction. When they did take such positions, they often took roles directly related to scholarship and learning. They served both the king and people with loyalty and diligence, making seonbi easy targets during purges.

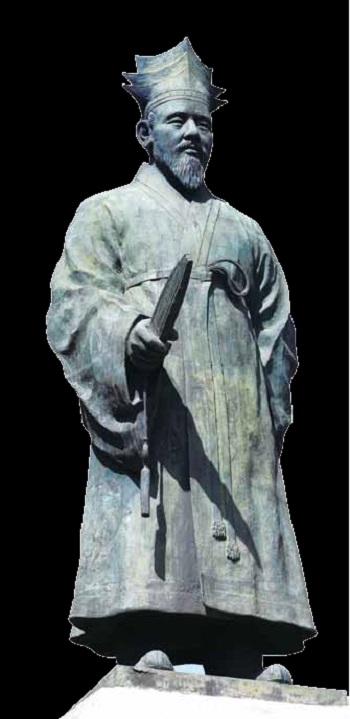

Yi Hwang, a renowned Confucian scholar. © Yonhap News

Outside of government, seonbi often sought teaching positions in order to share their education with the next generation. To the seonbi, spreading knowledge and virtue was just as important as cultivating virtue in oneself. In “The Traditional Education of Korea” (2006), Choi Wan-gee writes, “Naturally, the cultivation of a true seonbi accounted for the larger part of education in Joseon, a society ruled by the Neo-Confucian ideology and the sadaebu (aristocratic) class. Thus, the seonbi was both the provider and receiver of education.”

The way of the seonbi was closely intertwined with the development of a particularly Korean style of educational institution, the seowon. First appearing in the middle of the 16th century, the seowon were private Confucian academies that functioned as both Confucian shrines and places of learning where students prepared for the Joseon Dynasty’s all-important civil service exam. Many were established by either leading scholars or their students; Andong’s famous Dosan Seowon, for instance, was founded in 1574 by the disciples of Yi Hwang, one of Korea’s two greatest Confucian scholars. Attended by the children of the sadaebu class, these academies nurtured the intellectual talent pool from which the seonbi emerged.

The seowon were also great architectural accomplishments, and are so important to Korea’s cultural and social history that they were added to UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list in 2011 with the following explanation: “As the center of local culture and society, seowon produced a wealth of collections of literary works and publications. They served as a gathering place for intellectuals, where public opinion and sentiment were concentrated; as a place for social education, where rituals and lectures were provided; and, finally, as libraries and publishers for local society.”

This cultural emphasis on learning and the high value placed on education, based on the Joseon Dynasty’s seonbi spirit, continues to this day and is the foundation upon which rests modern Korea’s academic success.

Education: Engine of Growth

It would be an understatement of epic proportions to say that the first half of the 20th century was unkind to Korea. Imperial rule, national division and fratricidal war left the nation shattered. Korea possessed little in the way of industry, public infrastructure or national resources, and was acutely dependent on international aid for its survival.

In just half a century, Korea rose from the ashes of war and crushing poverty to join the ranks of the world’s developed nations. In 2009, it became the first former aid beneficiary to join the OECD Development Assistance Committee, a gathering of wealthy donor states. At the heart of this meteoric rise was education. The only way Korea could improve the quality of its human resources, virtually the only resource available to the country in its hardscrabble post-war years, was to educate them. Beginning in the 1960s, the government worked hard to ensure that all children received a basic education. As the economy advanced, the government invested more in science and technology, creating KAIST (the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology) in 1971 and building a number of government-sponsored research institutes.

Fortunately for Korea, the nation had a Confucian tradition of education on which to fall back. This tradition, when combined with society’s much documented zeal for education, allowed Korea to substantively improve its labor force, enabling both industrialization and, ultimately, a leap to a knowledge-based economy.

One phenomenon upon which observers have frequently commented is the Korean passion for education. By the 2000s, the average Korean family was spending a much larger proportion of its income on education than in any other country in the world. On the political spectrum, reforms in education policy often cause extended ripples throughout Korean society, with the public generally taking a strong interest in anything that influences education, at any level. This is particularly visible in print media, which run articles on education much more frequently than media in other countries. Another significant difference is the extent to which educational expenses are deductible from national income taxes. In addition to this rebate, the Korean government has demonstrated— across political parties—a willingness to invest in educational reform projects, the latest of which is a plan to switch from paper textbooks to electronic textbooks starting in 2015.

A ceremony in honor of Yi Hwang at Dosan Seowon. © Yonhap News

Top of the World

Koreans’ passion for learning, when combined with other forms of public investment in education, yields impressive results. Korean students routinely score at the top of world tests for educational achievement. The scores from the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), an international standardized test designed to evaluate education systems by testing the abilities of 15-year-old students worldwide, show that, among the 64 nations in the survey, Korean students ranked fifth in math and reading and seventh in science. That same year, the United Nations Human Development Index, which analyses quality of life in developed nations using a variety of indicators, ranked Korea as number 12 out of the 185 member nations in the assessment. According to the results, the reason for Korea’s high rank is its educational achievement.

Despite dramatic social changes across society since the country’s economic development began in earnest in the 1960s, the Confucian tradition of respecting teachers lives on. University professors, in particular, have high social status. Foreign professors at Korean universities, a population that has greatly increased in size in recent years, often remark on how pleasant Korean students are to teach because of their good classroom manners and deferential attitude.

Another remarkable aspect of Korean education is the prevalence of continuing education programs in companies and government institutions. Some programs consist of several days of lectures, whereas others are much longer, lasting up to several weeks. Many of these offerings are designed to upgrade employees’ knowledge and skills, a reflection of Korea’s desire to stay at the forefront of new development. This interest in lifelong learning also reflects the Joseon-period ideal of education as a tool for moral cultivation and for becoming a better person. Aside from formal, continuing education programs, it is not uncommon for Korean adults to attend classes relating to hobbies and pastimes, as well as a variety of public lectures and cultural events.

The World Takes Notice

Korean society’s enthusiasm for education, and the results it has produced, has grabbed the world’s attention. One need not look any further than U.S. President Barack Obama, who has repeatedly cited Korea as an example of academic excellence from which Americans should learn.

President Obama is not alone. In a speech in January 2014, United States Secretary of Education Arne Duncan made explicit reference to Korea’s status as the nation with the highest university graduation rates: “That Number 1 spot is now occupied by—guess who?—South Korea. So, you may be asking: What are countries like South Korea doing for their kids that we aren’t? The answer is, a lot.” Addressing the third Korea-Africa Forum in Seoul in October 2012, Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs pointed to Korea’s zeal for education as the secret to Korea’s economic success over the last five decades.

Outside of standardized testing, Korean students are also routinely winning other types of international academic competitions. In 2012, Korean high school students won six gold medals at the 53rd International Mathematical Olympiad in Mar del Plata, Argentina. In 2014, Korea added to its already impressive PISA performance by taking, along with Singapore, the top spot in the OECD’s first PISA problem-solving test. Some 85,000 students from 44 countries took the computer-based test, which uses real-life scenarios to measure the skills young people will employ when confronted with problems in their everyday life. According to the OECD, Korean students are, “quick learners, highly inquisitive and able to solve unstructured problems in unfamiliar contexts.”

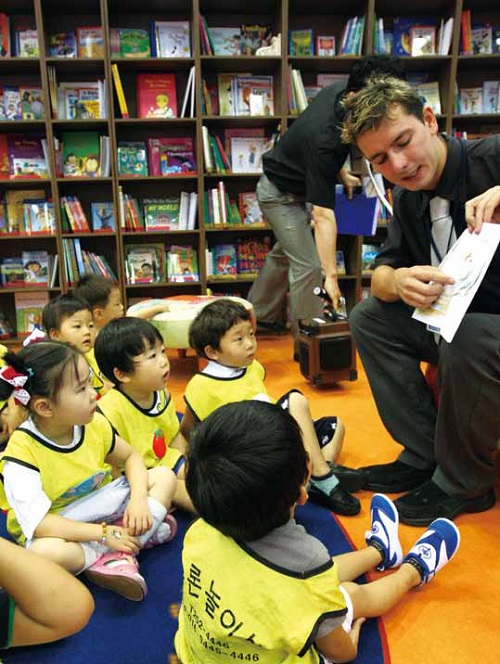

Youngsters learn English at an English language kindergarten. © Yonhap News

An Enduring Tradition

In looking at Korean education over the course of history, several major themes come to the fore. The first, and most obvious, is the endurance of the Confucian tradition. A formal education based on the classic Confucian texts and values became dominant early in the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) and lasted for another 1,000 years until the end of the Joseon period in 1910. This system of education was based on mastering the ability to read classical texts and to write original texts in classical Chinese. This was not an easy task, and a system of schools was created to support the development of these skills. The emphasis on literacy stimulated the writing of a large number of texts, including the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, an extensive set of books containing detailed records of the king’s official activities from 1392 to 1863 that was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 1997. The long tradition of detailed reading of texts and reverence for learning itself has served Korea well in its effort to acquire information needed to support the drive for economic development since the 1960s.

Another enduring trend is the tension between public and private education. During the Joseon period, private academies and schools began to dominate. During the dark years of Japanese colonial rule, private education, particularly Christian schools, stood as implicit resistance to Tokyo’s ruling ideology. In the 2000s, private education became dominant for its assumed competitive advantage.

Together, the enduring Confucian tradition and the availability of both public and private options contributed to a unique intellectual climate that has helped propel Korea into the super elite group of democratic nations with more than 50 million people and a per capita GDP of more than USD 20,000. Perhaps more than any other nation, education remains central to the story of achievement in Korea, and will most certainly play an equally important role in the future.

* Article from Korea Magazine (June 2014)