Korean Peninsula was ‘a land of leopards’

One may think of tigers as the fiercest animal that ever lived on the Korean Peninsula. There was, however, another species of large cat that was just as fierce as tigers, and even outnumbered them. They were leopards.

In Joseon times (1392-1910), the number of leopards was large enough to enable royal families to bestow leopard skins as gifts for their retainers.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), the leopards in Korea belonged to a species subordinate to the leopards that inhabited the Russian Far East and parts of northeastern China.

Only 50 or so leopards are believed to exist belonging to this subspecies common to the Korean Peninsula, the Maritime Province in Russia and to Jilin Province in China.

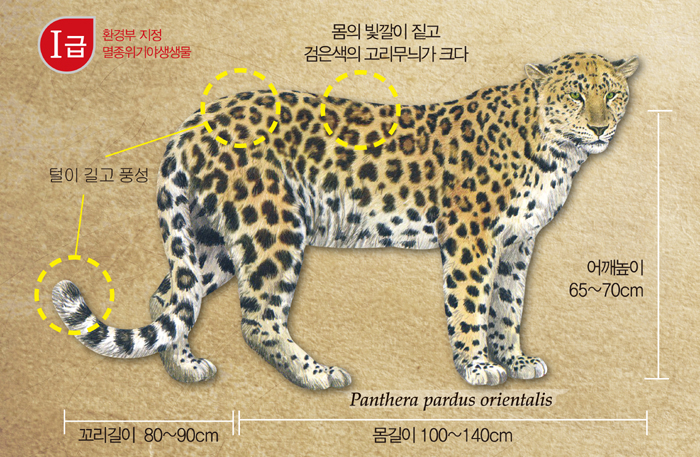

As seen in the above image, Korean leopards are characterized by darker fur and bigger ring patterns in their hair with long, abundant fur on their tail. The body is 100 to 140 centimeters long while the tail can be 80 to 90 centimeters long.

The animal was the most feared creature in ancient Korea, at the top of the peninsula’s natural food chain, but it is now on the verge of extinction.

There’s a special exhibition underway in Incheon that is shedding new light on this endangered large cat.

The “Forgotten Name, Korean Leopards” exhibition kicked off on December 10 at the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR). It features a wide range of records concerning the animals, stretching from merely a decade ago back into Joseon times. The exhibit runs until March 31 next year.

With a glimpse at the traces of this animal on display here, one may soon find that the Korean Peninsula — even up until just a decade ago — was a land of leopards.

According to statistics released by the colonial era Governor-General of Korea, the number of leopards that were captured in the 23 years following 1919 came to 624, six times higher than the number of tigers captured in the same span between 1919 and 1942.

Among the exhibits on display, there’s a newspaper clipping that reported on the capture of a mature male leopard on Yeohangsan Mountain in Haman, Gyeongsangnam-do (South Gyeongsang Province), on March 4, 1970.

There are 18 more documents that record leopards seized in the south of the peninsula after liberation in 1945 up until the 1970s. The records prove that the animals existed across the peninsula, even as recently as the 1940s. The last capture of a tiger was in 1921.

The “Forgotten Name, Korean Leopards” exhibit is underway at the National Institute of Biological Resources.

Exhibition-goers will get a glimpse at more newspaper clips and images related to the large cat dating back from liberation in 1945 onward, as well as records that spanned Joseon times and during Japanese occupation.

There are video clips on display showing vivid images of Korean leopards that were filmed in Russia’s Maritime Province, as well as the animal’s current conservation status in the region.

Visitors touch a virtual leopard using 3-D computer graphics at the “Forgotten Name, Korean Leopards” exhibition.

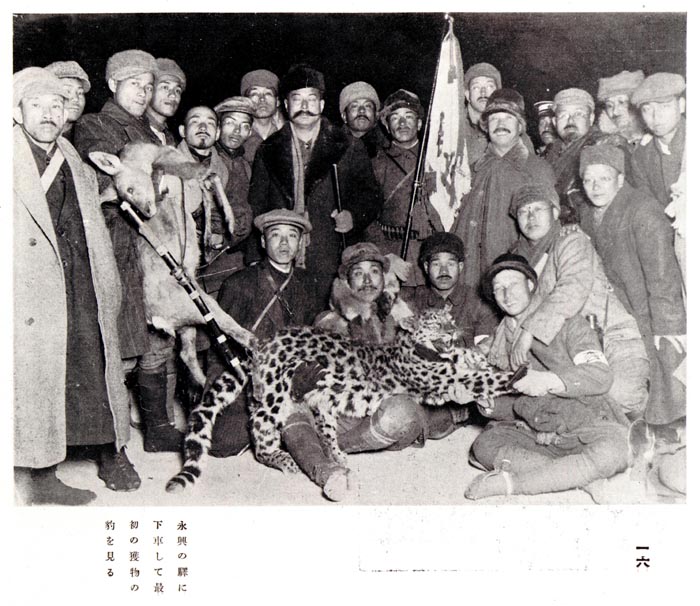

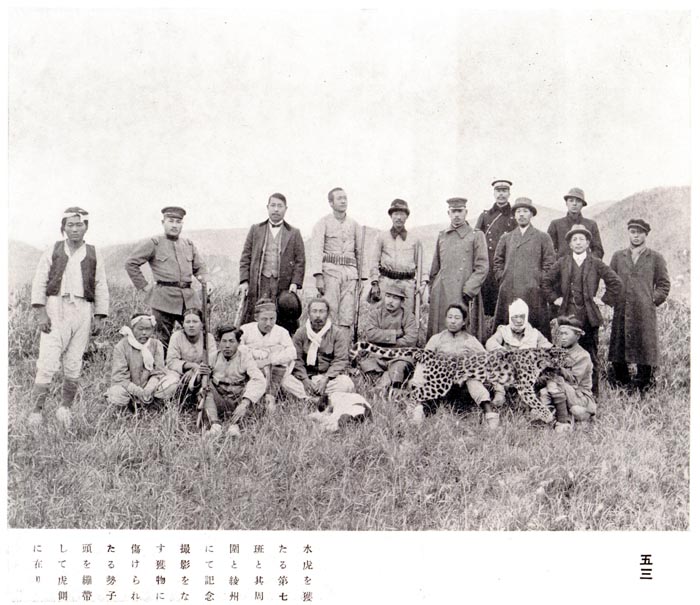

In addition, an original copy of a rare book about Korean leopards and tigers,“Jeonghoki” (征虎記), written in early Japanese colonial times, is on display.

The volume was written by Tadasaburo Yamamoto, a businessman. For a month in the winter in 1917, he formed a hunting group called the “Jeonghojun” to capture leopards and tigers. He recorded his month of hunting activities in the book.

The book ‘Jeonghoki‘ (征虎記) from colonial times covers a month-long hunt for leopards and tigers across the Korean Peninsula, with images as seen above.

The official poster for the “Forgotten Name, Korean Leopards” exhibition.

“By highlighting the image and value of Korean leopards, a species which has been little-known until now, this exhibition will help the public understand the natural ecosystem across the peninsula and to feel the need for conservation of biological resources,” said NIBR President Kim Sang-bae.

By Sohn JiAe

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: the National Institute of Biological Resources

jiae5853@korea.kr