Gat, traditional headgear in Korea

The world of hanbok is broad and deep. Like any collection of fashions, it has its variations, but a dapper Joseon-era man would always take care to wear his gat.

Take a look at some Joseon Dynasty paintings. They show us the street scenes of the time: what people wore, what they did, how they dressed, how they played. “The Welcome Parade for the Governor of Pyeongan Province” (Pyeongan-gamsa-hwanyeong-do) would be a good place to start. It was painted by Kim Hong-do (1745-1806). It shows a group of nobles lined up outside the palace, welcoming a provincial governor to the capital. Take a good look at the figures in the painting. All the men are wearing a gat.

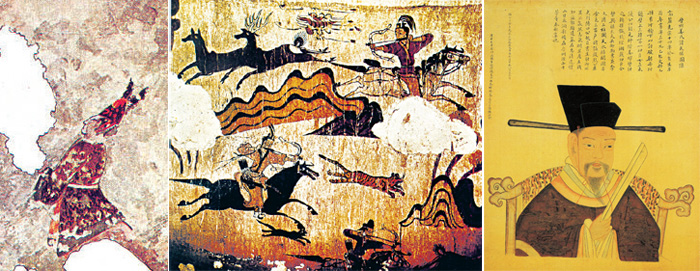

A picture of three Korean scholars wearing black horsehair hats, drawn by an unidentified Western visitor in 1895

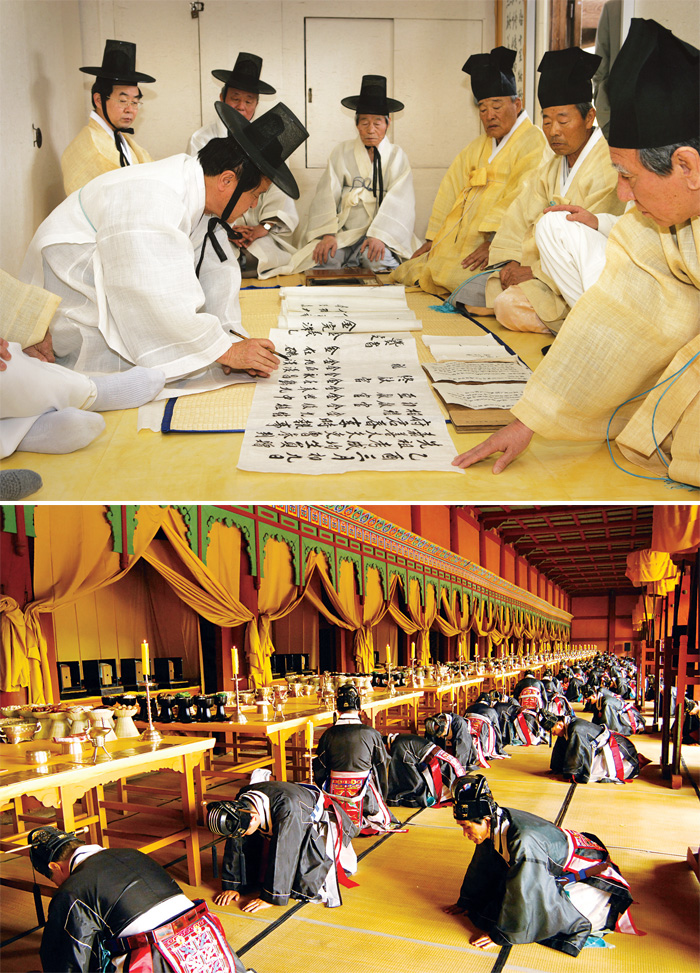

The gat can be thought of as the representative headgear for traditional male Korean attire. It’s a large round black-and-white hat, who’s delicate and elegant features are said to represent one’s intrinsic beauty. Like well-polished shoes today, a man took care of his gat. During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), commoners and nobles alike, and scholars, too, wore a gat just about every day. It was worn on their days off but was also part of a man’s ceremonial formal wear. During Confucian ceremonies, when bowing to the ancestors or to one’s parents, a man would wear a gat, too.

Traditional male formalwear consisted of a pair of trousers (baji), a shirt-like upper garment (jeogori) and a jacket-like outer garment (po). The gat, on top, completes the outfit. A man might add an overcoat (durumagi), as well. Kim Hong-do’s “The Welcome Parade…”, mentioned above, shows the whole crowd, aside from the arriving governor himself and his immediate entourage, dressed in white robes with a black gat. It illustrates how middle-aged men would never forget their durumagi, the overcoat, or their gat when they headed out to public events. The gat was an essential part of a man’s wardrobe and was versatile enough to suit the whole variety of male fashion as it existed during the Joseon era. In fact, you could say that men wore their gats for all five hundred years of the Joseon Dynasty.

Much like today’s modern Koreans, the Joseon people were quite fashion conscious and knew how to match their gat with the rest of their wardrobe. Hats and headgear as a whole occupied a significant place in the history of Korean fashion. Wearing something on your head was essential. A whole variety of headgear existed: jeolpung, sogol, chaek, jougwan and so on. There was the more modest geonand the metal bogwanryu-style hats. These last are elaborately decorated and are usually found in royal tombs. Most of that traditional headgear shared a basic triangular frame, embellished with bird feathers and other decorations. In fact, bird feather rituals (jousik) connote a form of bird worship, often connected with other concepts such as sun worship and immortality. Feathers were a common feature at ceremonial rituals. The official hats worn during the jousik ceremonies, the ancestral rites, had feathers and were much fancier than the jeolpong or sogol, which had no feather decorations. In later designs, the official hats even featured metal feather-like decorations.

Well before the Joseon era, the bokdu was already a type of men’s headgear popular in the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Think of it like a Victorian top hat, but not quite as cylindrical. It was a little more square and had a notch, or step, in it above the forehead. It was tightened at the back and allowed the man’s long hair to be kept neatly underneath, up on top of his head. As the fashion developed, some years later the four corners where sliced to make gak, a sort of tassel or strip of strengthened fabric that stuck out over the shoulders.

During the Silla Kingdom (57 B.C.- A.D. 935), royalty imported more from Tang China than just soldiers; it also imported Chinese fashion. After Silla’s defeat of Baekje in 660 with the aid of Tang troops, the peninsula was united under Silla rule. With a new dynasty, came new fashion and the official headgear policy changed. The bokdu top hat was chosen as part of the official dress code for the Silla court. Indeed, it was already part of the official court uniform during the reign of Queen Jindeok (r. 647-654). It was worn by royal aristocrats, court musicians, servants and slaves alike. But the different castes were required to have their bokdu made out of different material. It seems as if people have always used clothing to delineate class.

Moving some 200 years forward, during the later Silla era there were edicts passed in the 800s concerning one’s choice of headgear. Two years before his death, King Heungdeok (r. 826-836) issued a royal proclamation in 834, the eighth year of his reign, revising the colors of the official dress. Part of this was a restrictive proclamation, once again cementing one’s social class with one’s attire. The highest ranked citizens, the jingol daedeung, were allowed to use any material they wished for their bokdu top hats. The next six strata, or dupum, of society were only allowed to use finely meshed silk. The subsequent four dupum could only use course, thin silk. Commoners were only allowed roughly spun silk.

(From left) Gaemachong grave mound (jougwan); Muyongchong grave mound (jomigwan); Gang Min-cheom (963-1021) (bokdu)

During the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), bokdu of different material and shape would be worn by the king and his bureaucrats. This was part of their official dress and depended on their rank. These varied from the jeongak bokdu, with the gak strips protruding at right angles sticking out above the shoulders, to the jeolgak bokdu, which had the gak pointing diagonally downward, as well as the chaehwa bokdu, a third variation. Think of it as the difference between an Oxford, a Brogue and a Derby: all subtle variations in men’s fashion.

By the time of King Gojong’s reign (r. 1863-1907) at the end of the Joseon era and just before modern times, hierarchical distinction with regards to a man’s bokdu had largely disappeared and even servants were permitted to wear the tall headgear.

There are many ancient paintings we can use to compare traditional bokdu styles. Two exemplary samples are from the 11th and 14th centuries. There is a portrait of King Gongmin (r. 1351-1374) in the Jongmyo Shrine in Seoul. It depicts the monarch dressed in adanryeong, a type of loose robe with rounded sleeves worn by officials and royal figures, and sporting a bokdo atop his head. Compare this to General Gang Min-cheom’s (c. 963-1021) funerary portrait, in which he also wears a bokdo. In the king’s portrait, painted around the time of his death in the 1370s, you can see that the gak strips on either side of his bokdu top hat are wider and somewhat shorter than the longer thinner gak found in the general’s portrait, completed, some 350 years earlier in 1021. Furthermore, in the later king’s portrait, there is a small decorative knot in the step of the hat. The earlier general’s portrait has no such decorative knot.

Much as the earlier Silla interacted with the Tang, so too did the later Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) interact with its neighbor, the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The late-Goryeo era saw the introduction of various Yuan customs, including dress and attire. Where the earlierbokdo top hat was squared and stepped, the later balip top hat was much more cylindrical and even more like a Victorian top hat. Thebalip was worn by Yuan officials and it was the next wave of male headwear fashion.

The balip itself was later modified with some decorations and was re-named a heukrip. Only officials of the baekkwan social rank were allowed to wear the heukrip. Indeed, it was the introduction of the balip at this time that led to the cylindrical top hat becoming the official dress code for baekkwan-ranked officials and, eventually, led to the top hat’s popularity in later Joseon culture.

But at first, the balip was a rounded, half-sphere hat with a narrow brim, sometimes embellished with a jewel on top. The crown is flat and round, as is the brim. Think of it like half a sphere, upside down. In the portrait of Yi Po (d. 1373), a Goryeo era bureaucrat, he can be seen wearing a dark green robe and a Mongolian-style balip. Such traditional balip can also be seen in the portraits of Yi Jo-nyeon (1269-1343), another Goryeo era official, as well as at the burial site of Bak Ik (1332-1398), whose grave was only discovered in 2000 in Miryang near Busan.

(From left) Jeong Mong-ju (1337-1392)(samo); King Gongmin (r.1351-1374)(bokdu); Yi Po (?-1373)(balip)

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) society was quite hierarchical with little or no movement between the strata: the randomness of your birth determined, for the most part, your life path. Tied in with this were concepts of Confucian values and Confucian relationships. Indeed, the Joseon era placed an emphasis on Confucian values and the strict separation of society’s castes. One of those values was the importance, nay the need, to dress with propriety and to dress properly; thus, the evolution of the hat’s importance.

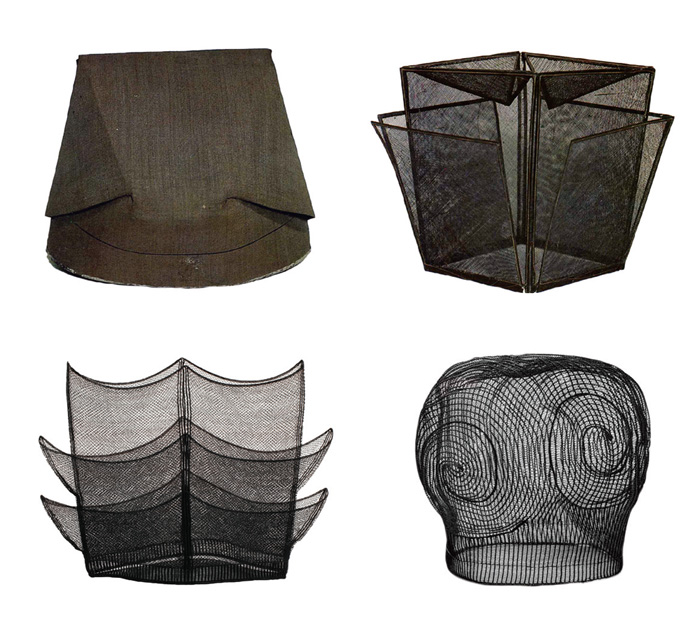

(From left to clockwise) Jangbogwan (Korea University Museum); Heukgeon (Korea University Museum); Wongwan (Scholar’s headdress); Jeongjagwan (Men’s indoor headdress)

Joseon-era hats varied widely, ranging from the flat-brimmed pyeongnyanja, such as the paeraengi, the chorip, the heukrip, the baekrip, the jurip, the okrorip and the jeonrip, to the brimless bangnip, such as the banggat and the sakkat. Each style of hat was used for a different purpose and by a different rank of society.

Among this plethora of headgear, however, the heukrip stands out. It was the most versatile of hat styles, used as part of everyday dress for men from a variety of castes, and was an indigenous development: the Joseon people took this hat style and made it their own.

Part of the problem around headgear was the strictly ranked society and the formalness of one’s everyday behavior. Since Joseon-era aristocrats were even expected to dress formally when relaxing at home, the necessity arose for a much more comfortable headgear to replace the gat. Therefore, the nobility began to wear the various hats introduced from Ming-era (1368-1644) and Qing-era (1644-1912) China. These included the square-shaped banggwan and sabanggwan, as well as the dongpagwan, the waryongwan and thejeongjagwan. The popularity of these hats may have been due to Confucian influences and the fact that these styles were worn by literary and scholarly figures during the Ming and the Qing. Or, perhaps they were just more comfortable.

Toward the end of the Joseon era, the Daewongun (r. 1863-1873) decreed that people should dress more modestly. His new dress code replaced the larger gat with smaller versions of similar head gear. Then after the Gapsin Coup (started December 4, 1884), when modernizers seized the main palace in Seoul and aimed at social as much as political revolution, Western hats began to dominate male fashion. The gat began its path toward becoming a relic.

(Top) Rites held at clan family; (bottom) Royal ancestral rites in Jongmyo shrine

Finally, as the 1800s turned into the 1900s, there was a decree requiring all men to cut their hair. This did away with the traditional top knot, allowing hats to become a quasi replacement for long hair. The newspaper, a new fangled item in and of itself, began to print advertisements for bowler hats, fedoras, flat caps, Gatsbies, porkpies, homburgs and even hats for ladies. The ad slogans celebrated these Western hats as being gifts from civilization. In reality, a range of hats had always existed to suit all forms of dress up through the Joseon period. The gat was as varied in its use, depending on social caste, status and purpose, as were all the Western imports.

With the advent of the 20th century, the dress code continued with its alterations. Officials began to wear Western suits on official occasions. This, in turn, brought about the wearing of Western hats. Government bureaucrats began to wear early forms of fully Westernized formal dress: the British gentleman’s three piece suit. The deerstalker had a brief period of popularity, sometimes with a decorative feather. On less formal occasions, officials wore frock coats with silk hats imported from Britain. Many schools and institutions began to introduce Western clothes as part of their uniforms. Even when still wearing traditional Korean clothes, a man might complete it with a Western hat.

As society modernized, so too did one’s fashion. During the Joseon period, the dress code was imbued with all the ideal Confucian values of order, discipline, hierarchy and formality. A formal and proper outfit would be worn by a man with dignity and authority, and the hat played a role in this. But modern society—a bustling, complex society, with people from the towns moving to the cities and the cities growing and industrializing—would no longer accommodate the brittle strata of ancient Joseon.

As Western fashion– that is, mostly British, Victorian-era fashion– made inroads into old Joseon, the hat was reduced from being the identifier of one’s caste to being a mere fashion item, with no symbolism or meaning. It now simply reflected the trends of the time. It no longer held social significance. The hat no longer makes the man. It’s just one more item, like cufflinks or a watch, which he can add to his wardrobe.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

(Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)