Alcohol in Korean life 1

Sul, the general purpose Korean word for all types of alcohol, is a much more romantic and culturally meaningful word than its English language equivalent, alcohol. Sul implies a culture, a sharing between friends, whereas the English “alcohol” can be somewhat scientific or cold, or even damning. “A pint,” in the British sense, carries the same friendliness and warmth that sul does, or perhaps the Australian “stubby”. Sul implies the artistry and care of a Portland craft beer, the hands-on approach of a Tennessee boutique distillery, the aged vines of a Burgundy terroir and the tradition of a Highlands malt.

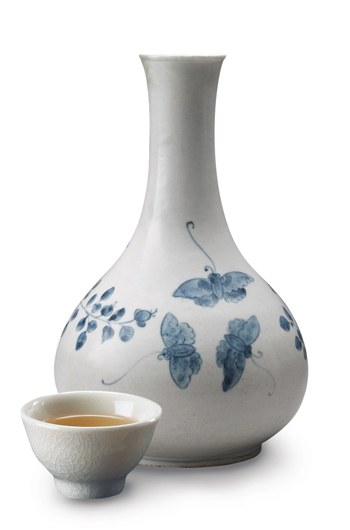

Sul has long been an integral part of Korean life. In ancient times it was thought of as a medium of communication with the gods. Drinks and drinking, since time immemorial, have occupied a special place in rites of passage and seasonal customs. Profound significance and special attention has always been accorded to the ways in which drinks of various kinds are prepared, to what style of vessel will hold the drink and to how the drinks are served. This has given birth to a variety of artifacts and manners, ascribing meanings the roles of alcohol and the many ways in which it appears in society. Understanding the history and cultural value of sul, that is, untangling all the strands and strings that involve men, women, drinks, drinking and all the many facets of human existence, will contribute to a better appreciation and enjoyment of traditional Korean alcoholic drinks.

Why did the early Koreans make sul?

Making quality sul was far more difficult than cooking food. It required a successful period of either fermentation or distillation. Without the benefits of modern science, our ancestors believed that what determined the flavor and fragrance of a drink were divine powers, not human endeavors. This is why the verb “to pray”, bil-da or bit-da, can be used in various expressions to imply the brewing or distillation of grain or fruit. The verb can be interpreted in any number of ways.

The ancestors prepared for sul-making by praying to the gods to help them make a quality tipple. They believed divine power played a significant role in the brewing process and marveled at the fermentation process. We now know that microorganisms produce alcohol along with a range of flavors and fragrances, surpassing those of the original ingredients. The ancestors, however, believed that though humans made the effort, it was the gods who determined the results. The ancient brewers would cleanse their body and their mind and wait for divine results. They prayed for a communion with the gods by offering up some alcohol. Booze was regarded as a beverage for the gods, not for humans. After an early harvest, the best grain was chosen to make sul and to offer it to their gods.

Early Koreans would make grain-based alcoholic drinks to pray for good fortune. Good fortune, it was believed, would come to those who drink.

Different techniques and ingredients were used depending on for whom you were making it and for what purpose. Variables included: whether it was being brewed for ancestors who have passed away or for live, human drinkers; whether for family elders or simply for guests; whether it would be used in a farming prayer ritual or festival or intended for sale or as a gift.

Up to a mere 80 or 100 years ago, each family maintained its own secret brewing recipe, just like a Western family might have its own special lasagna recipe or barbecue sauce secret, passed down by grandma or grandpa. Alcohol made at home was used to pay tribute to the ancestors during the yearly rituals. It was used when praying to the numerous nature gods and spirits. It was used for festivals and for farming rituals where one would pray for a good harvest. Homemade booze was also offered to guests. The wide varieties of sul were all made at home, depending on who would consume it. It was always, of course, served with exquisite manners and following strict rules.

An early concept of alcohol

Our ancestors thought of sul as “fire contained in water.” As the drink underwent fermentation, microorganisms converted sugar into alcohol, along with carbon dioxide. This, in turn, generates bubbles. As they saw their sul concoction bubble up, our forefathers assumed that, out of nowhere, fire was coming into being. Their concept of sul was also based on the traditional East Asian principle of yin and yang: cool and calm water was represented by yin; hot and rising fire was represented by yang. Sul was regarded as the perfect combination of yin and yang.

The abalone-shaped water channel at the site of Poseokjeong Pavilion

Imbued with its unique taste and scent, each kind of sul contains its own unique characteristics, characteristics that cannot be found in the original ingredients. Alcohol warms the body, lifts the spirit and sometimes addles the brain. It emboldens you to say or to do what might be considered abnormal or not quite politically correct or socially acceptable. Sul was consumed not to get drunk but to be enjoyed as a gift from the gods, with a balance between yin and yang.

Brewing and distilling belonged in the domain of the divine, not the human. Humans would merely do their best to ensure good conditions for the booze-making process and learn the relevant skills. But it’s the godly power that makes quality swill. When brewing or distilling, our ancestors completely engaged their hearts and minds, immersed in the process, praying as they did so. It was a religious process. When the drinks were completed, they would drink their rice beer and other tipples, getting connected with the gods. They would dedicate their drink to the gods and spirits, praying for the health and prosperity of their family, offspring and friends.

Etymology of the word

The original term sul is associated with the ancient Korean concept of fire coming out of water. The two Korean words for water and fire were joined together to create the then-new term sul. The word su means water. The word bul or bool means fire. They were combined to become su-bul which was then pronounced su-eul¬ and thence sul.

A second hypothesis posits that the term sul originated from the Chinese characters 酥乙, or su-eul, meaning tarakjuk, a Korean milk porridge, and a bird. This hypothesis assumes that sul was first found in leftover milk porridge which underwent fermentation after some bird droppings accidentally fell into it.

The etymology of the term sul suggests that the beverage was spontaneously created in Korea, as it was probably independently discovered in many separate parts of the world. Fungi or bacteria from the air could have fermented the sugar in fruits or grains and produced alcohol. The ancient Koreans re-created this accidental process and developed methods to brew alcoholic beverages.

Historical documents tell the tale

The oldest record of alcohol in Korea is found in a story about the founding of the Goguryeo Kingdom (37 B.C.- A.D. 668). TheSamguksagi text, or The History Of The Three Kingdoms, was compiled in 1145 during the Goryeo Dynasty and related many stories from the much earlier Goguryeo Kingdom.

The story goes something like this:

Haemosu, the son of the God of Heaven, invited the three daughters of Habaek, the water deity, and treated them to some drinks. When the three daughters were about to return home, he seduced the eldest daughter, Yuhwa, and they spent the night drinking together. Thereafter, Yuhwa gave birth to a child, Jumong, who became the future founder of the Goguryeo Kingdom.

During the almost one thousand-year span of the Three Kingdoms (57 B.C.- A.D. 935), brewing techniques were perfected. The Goguryeo had a custom of eating porridge or steamed grain powder with milk. This dietary practice arguably led to the discovery of alcohol, which corresponds with the etymological theory, above. Historical writings note that, “People from Goguryeo defeated the ruler of Yondong of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.- A.D. 220) by brewing jiju, an alcoholic drink,” and that they, “enjoyed the consumption and storage of fermented foods.”

There is also a record showing that the ancient states of modern-day Japan learned brewing skills from the ancient Koreans. An ancient Japanese text from the early 700s is the Gosagi, or Kojiki in Japanese; the “Historical Stories” or the “Record of Ancient Matters.” This oldest existing Japanese text notes that, “Inbeon from the Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C.- A.D. 660) transferred techniques for making sul to Japan, drinking it like a ‘liquor deity.’”

During the Goryeo Dynasty (918- 1392), brewing methods for grain alcohol were perfected. A new technique, distilling, was adopted. The categories of alcohol diversified into several groups, including cheongju, a clear spirit, takju, a thick rice beer, soju, a clear distilled spirit from sweet potatoes, and gwasilju, a wine-like drink made from fruit.

During the Goryeo Dynasty, culture was heavily influenced by Buddhism. Temples, the traveler’s hotel of their day, sold liquor on the sidelines of their principal business, lodging. State-run public drinking houses were built in order to promote the circulation of the government’s new currency, the haedong tongbo. The rise of trade and the development of a merchant class also contributed to the tavern boom.

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), traditional liquor culture flourished and reached its peak with the advancement of home brewing by private families. The compilation text Dongui bogam, or the Exemplar of Traditional Korean Medicine, assembled in 1610, promotes the creation of a new type of liquor by using medicinal herbs. The appearance of sojutgori, or distilleries, boosted the consumption of the sweet potato-based booze, soju. Like a grand Gatsby party, the aristocratic classes indulged themselves in a variety of luxury alcohols.

Each region of the country developed a particular type of liquor distinguished by its own regional characteristics. The southern region was renowned for takju, the middle region for yakju, a medicinal spirit, and the northern region for soju. The multiple fermentation technique was the most widespread method of brewing. An alcoholic drink that mixed a brewed beverage with a distilled spirit was prevalent in late Joseon, similar to the mixing of beer and soju today.

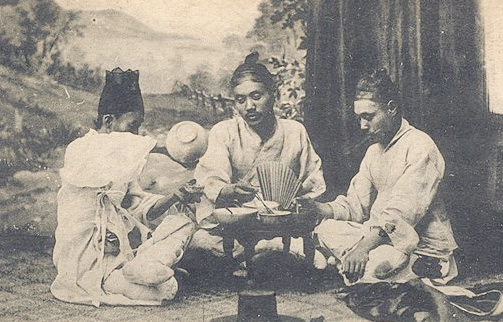

Drinking at a jumak, a public house, during the Daehan Jeguk (Great Han Empire)

As with many cultural features, a traditional liquor culture that dated back thousands of years was ravished during Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). A decree levying a liquor tax was announced by the colonial government in 1907. It banned home brewing and allowed only licensed brewers to make liquor, driving thousands of traditional alcoholic beverages into extinction. With the adoption of another liquor tax law in 1916, the colonial rulers tightened the crackdown on what they viewed as illegal alcoholic beverages. They reduced the number of officially sanctioned liquor categories to a mere three: yakju, takju and soju.

Even after liberation in 1945, colonial era liquor tax laws were still enforced. Food shortages during the Korean War (1950-1953) encouraged the government to maintain the crackdown on making moonshine: grain had to be eaten, not turned into drink. Liquor control was further strengthened by the adoption of a grain management law in 1965. During this tumultuous time, traditional booze lost much ground and its traditions and recipes faded into the mists of time.

Finally in the 1980s, the necessity to designate an official traditional liquor as a state heritage item was seriously considered. But the rupture in traditional culture of about 80 to 100 years has been hard to mend. Many skills and much knowledge involved in the making of traditional alcoholic drinks had been only orally transmitted, leaving few written records.

So this winter, you can be pleased that there has been some resurgence in the variety of liquors available in modern Korea. You can relax with a bottle of maggeolli rice beer from your neighborhood vendor, or you can go for maggeolli’s slightly thicker cousin,dongdongju. If you prefer clear liquors, there is the plum-based seoljoongmae or you can opt for a bottle of cheongha, a slightly sweeter cheongju-style of clear liquor. Stronger than cheongju, you have the various varieties of soju. Or you can relax with a medicinal bottle of baeksaeju. Whichever you chose, you can be pleased at the resurgence of some of Korea’s vast traditional sulculture.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

(Source:Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)